My next JAFF book will be set in Brighton. I know just about nothing about Brighton, so my research is going to go here. Hopefully I’ll help out another Regency romance author.

Brighton Pavilion

George hired architect Henry Holland to transform his Brighton lodging house into a modest villa which became known as the Marine Pavilion. With his love of visual arts and fascination with the mythical orient, George set about lavishly furnishing and decorating his seaside home. He especially chose Chinese export furniture and objects, and hand-painted Chinese wallpapers. From 1802 the Marine Pavilion was exquisitely furnished and decorated with Chinese wallpapers, furniture and objets d’art’.

A disastrous arranged marriage in 1795 with Princess Caroline of Brunswick failed to take George’s attentions away from Mrs Fitzherbert and his lavish Brighton lifestyle. Within a year the marriage had collapsed.

In 1808 the new stable complex was completed with an impressive lead and glass-domed roof, providing stabling for 62 horses.

In 1811 George was sworn in as Prince Regent because his father, George III, had been deemed incapable of acting as monarch.

During the Regency years (1811-1820) the prince’s heady extravagance at the Marine Pavilion was a constant source of gossip. He would think nothing of spending days riding, promenading and sea-dipping, and nights eating, drinking, partying and entertaining.

At that time the Marine Pavilion was a modest building in size, not suitable for the large social events and entertaining that George loved to host.

In 1815, George commissioned John Nash to begin the transformation from modest villa into the magnificent oriental palace that we see today.

George’s presence had an enormous impact on the prosperity and social development of Brighton from the 1780s.

Brighton’s population grew significantly, from around 3,620 inhabitants in 1786 to 40,634 in 1831. The rebuilding of the prince’s home provided work for local tradesmen, labourers and craftsmen.

The presence in the town of the court, George’s guests, members of society and the Royal Household provided invaluable business for local builders and the service industries.

Seabathing in Brighton

“Betwixt the well and the harbour, the bathing machines are ranged along the beach, with all their proper utensils and attendants. You have never seen one of these machines. Image to yourself, a small, snug, wooden chamber, fixed upon a wheel-carriage, having a door at each end, and on each side a little window above, a bench below. The bather, ascending into this apartment by wooden steps, shuts himself in, and begins to undress, while the attendant yokes a horse to the end next the sea, and draws the carriage forwards, till the surface of the water is on a level with the floor of the dressing-room, then be moves and fixes the horse to the other end. The person within, being stripped, opens the door to’ the sea-ward, where he finds the guide ready, and plunges headlong into the water. After having bathed, he re-ascends into the apartment, by the steps which had been shifted for that purpose, and puts on his clothes at his leisure, while the carriage is drawn back again upon the dry land; so that he has nothing further to do, but to open the door, and come down as he went up. Should he be so weak or ill as to require a servant to put off and on his clothes, there is room enough in the apartment for half a dozen people. The guides who attend the ladies in the water are of their own sex, and they and the female bathers have a dress of flannel for the sea: nay, they are provided with other conveniences for the support of decorum. A certain number of the machines are fitted with tilts, that project from the sea-ward ends of them, so as to screen the bathers from the view of all persons whatsoever.”

“Think but of the surprise of His Majesty when, the first time of his bathing, he had no sooner popped his royal head under water than a band of music, concealed in a neighbouring machine, struck up “God save great George our King.” [Fanny Burney – Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay Volume 5-6.]

During Jane Austen’s time, Brighton, a town along the south Sussex Coast and seen above in a John Constable painting, was the popular resort destination. Bath’s desirability had plummeted among the Ton, as it had gained the reputation of being a stodgy tourist attraction for the elderly and infirm. By the time the Prince Regent’s fashionable set frequented Brighton, it had grown from a sleepy seaside village of 3,000 in 1769 to a booming tourist town of 18,000 by 1817-1818.

The lengthening of the formal season helped in establishing Brighton as a holiday destination. By 1804 the season started late July and lasted until after Christmas, and by 1818 it had been extended until March. Visitors of note were always mentioned in Brighton’s newspaper, and there were a host of them

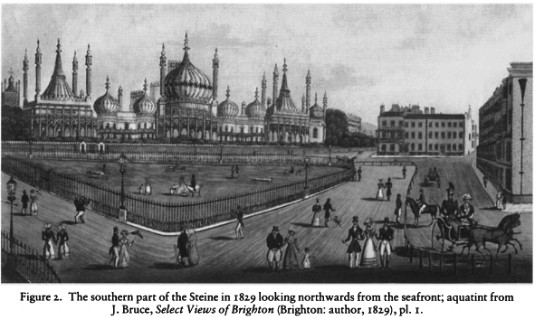

by 1810 guide books pointed out sites of interests in surrounding villages, amusements to be had, and picturesque walks. The sea was also used for entertainments such as yacht races and water parties which were watched from the shelter of the Steine. Military manoevres on the Steine and the Downs were popular.

https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/tag/regency-brighton/

Regency square –

Regency Square was built on one of the fields surrounding the fishing village of Brighthelmstone, the predecessor of modern-day Brighton. The field was named Belle Vue Field—probably in connection with the long vanished Belle Vue House, and lay to the west of the village.[6][7][8] The field ran down to the seafront, and was a popular site for travelling shows, fairs, military parades and other gatherings.[2] The field contained a windmill known as West Mill. A windmill was owned by Matthew Bourne in 1744, but was not marked on Ogilby’s 1762 map. A windmill is shown on Lambert’s View of Brighthelmstone which is dated 1765. The windmill stood in the field until 28 March 1797, when 86 oxen dragged it 2 miles (3.2 km) uphill on a sled to the nearby village of Preston.[9] It was re-erected there and renamed Preston Mill.[7] After several more renamings, it was demolished in 1881. Its machinery was cannibalisedby the owners of nearby Waterhall Mill.[10] A watercolour painting, now displayed at Preston Manor, shows crowds of people watching the mill’s removal to Preston.[10][11]

By the late 18th century, Brighton (as it was now known) had begun to develop into a popular and fashionable seaside resort.[12] Belle Vue Field became more important to the growing town in 1793, when in response to the increased military threat from France, a 10,000-man military encampment (Brighton’s first) was established there.[2]The camp quickly gained a reputation as a place for women to find partners, and Jane Austen used it as a setting in her novel Pride and Prejudice (written in 1796 and published in 1813). The heroine Elizabeth Bennet‘s sister is invited to Brighton and elopes with, and later marries, army officer George Wickham.[13] The camp moved to another site in 1794;[14] after returning to its former use as a fairground and showground, Belle Vue Field gradually lost popularity and was abandoned in 1807, when such entertainments moved to The Level, a large expanse of grass inland north of Old Steine.[7]

Shelling

Shell-work was another craft that proved popular. Ladies of the 18th and 19th centuries collected sea shells, often housing them in cabinets fitted with little drawers to take the different size shells.

Shell ornamentation was used on a great variety of objects. From a drawing room chandelier to picture and mirror frames. Then there were shell pictures; nosegays of natural colored shells in great variety. Many genteel females from the royal princesses to gentry were creating pictures and other clever things made of shells. Those who couldn’t get to the beach could buy collected packets of shells at various fashionable shops. Wooden dolls were sometimes dressed in shells. Birds, animals and people were also made out of shells. The dolls were the most popular in the early 19th century, made from common British shells. The dolls with their pretty enameled faces were too fragile for a child to play with, and I suspect they ended up beneath a glass dome to preserve them from little probing fingers.

Circulating libraries

In 1801, it was said that there were 1,000 circulating libraries in Britain. Book shops abounded as well, but in 1815 a 3-volume novel cost the equivalent of $100 today. Such a price placed a novel beyond the reach of most people. Worried about a second edition for Mansfield Park, Jane Austen wrote in 1814:

“People are more ready to borrow and praise, than to buy –which I cannot wonder at.”

Circulating libraries made books accessible to many more people at an affordable price. For two guineas a year, a patron could check out two volumes. Which meant that for the price of one book, a patron could read up to 26 volumes per year.

Jane Austen well knew the attractions of libraries at sea side resorts. Mrs. Whitby’s Circulating Library operated in Sanditon, and Lydia visited one in Brighton. In her letters to Cassandra, Jane frequently mentioned circulating libraries, in particular visiting one in Southampton.By 1800, most copies of a novel’s edition were sold to the libraries, which were flourishing businesses to be found in every major English city and town, and which promoted the sale of books during a period when their price rose relative to the cost of living. The libraries created a market for the publishers’ product and encouraged readers to read more by charging them an annual subscription fee that would entitle them to check out a specified number of volumes at one time. – Lee Ericson, The Economy of Novel Reading